Even more than 70 years after the end of the war, there are still numerous underground explosive ordnance in the Federal Republic of Germany. These pose a considerable risk to public safety (in particular life and health, freedom, property of individuals) or public order in the event of ground intervention.

In addition to various types of written sources, historical aerial photographs taken by Allied reconnaissance units are an essential medium for the reconstruction and spatial delimitation of areas potentially contaminated by ordnance.

Aerial photographs were usually taken in the run-up to attacks to identify possible targets, but also during or in the aftermath of bombings to "monitor success". In the Construction Guidelines for Explosive Ordnance Clearance (BFR KMR), aerial photographs are described as "objective "contemporary witnesses" of a region at the time of recording".

In addition to the effects of Allied bombing, they show other potentially explosive ordnance-relevant objects and structures such as various types of positions (cover holes, trenches, anti-aircraft positions, etc.), military facilities and areas (airfields, firing ranges, barracks, training areas) or even natural cavities in which explosive ordnance may have been placed.

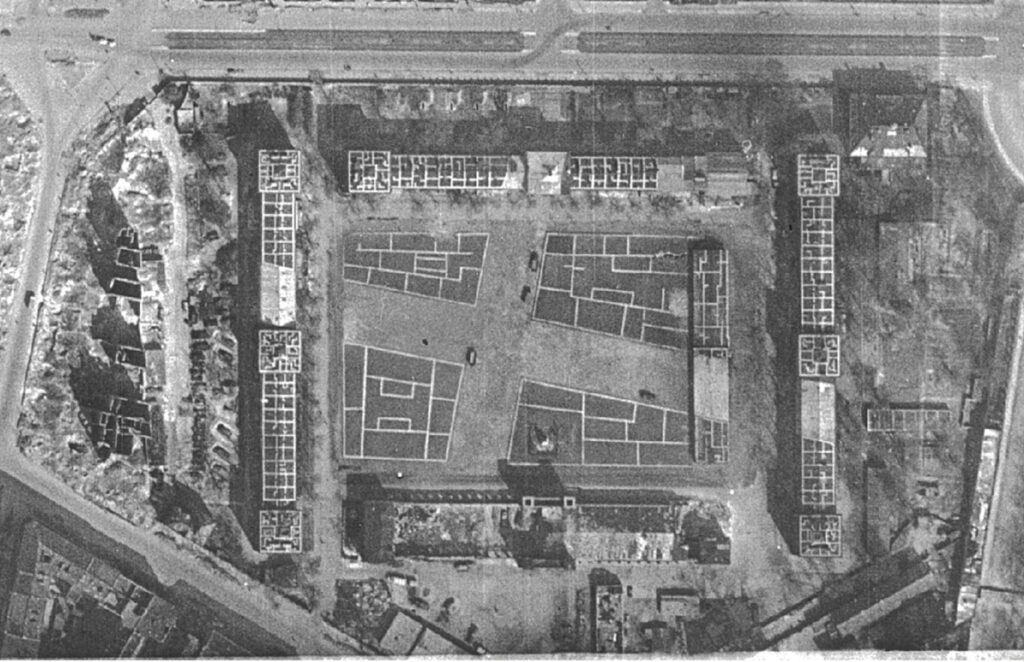

The interpretation of historical aerial photographs is not only made more difficult by poor image quality and/or image errors; the attempt to mislead enemy aerial reconnaissance through camouflage measures also poses a challenge for today's interpreters.

The camouflage and deception measures of the time were very varied and served different purposes.

In addition to concealing objects, camouflage and deception measures were mainly used to make it more difficult to identify objects (e.g. types of aircraft or ships), to prevent the detection of targets during bombing raids and to feign the existence of civilian or military objects, installations and facilities.

While it was still relatively easy to conceal smaller installations by using camouflage netting and branches or painting, for example, such projects were associated with immense challenges for larger objects or installations. In the knowledge that larger installations could not be completely concealed, the focus was often on giving them a different appearance to make them more difficult to identify.

The change in appearance was a widespread measure to make it more difficult to find targets during bombing raids. During the approach to the target, the navigators usually orientated themselves on prominent landmarks and architectural structures (e.g. conspicuous building structures, squares, bodies of water). Visual changes to these structures made navigation more difficult, which meant that the corresponding targets could only be recognised with a delay or, at best, not at all.

Another means of deception was the construction or installation of dummies. These could be individual objects such as dummy aeroplanes or anti-aircraft gun emplacements, but could also be large-scale dummy installations (e.g. oil tanks or factories). Such dummies were intended to simulate the presence of troops or potential targets. Deception and camouflage measures are usually easy for an experienced aerial image analyser to recognise during stereoscopic analysis and in the course of multi-temporal image viewing. However, in the absence of experience or an inadequate aerial image basis, they harbour the risk of fundamental misinterpretations, which in the worst case can lead to a correspondingly incorrect assessment of the suspected explosive ordnance.